The wide range of industries we serve necessitates broad materials testing knowledge as well as a dash of ingenuity – often times receiving newly developed materials or components. Arguably most important though, is an insatiable curiosity towards understanding how we interact with the products and materials we take for granted in their every day use. Any manufacturer knows that the it is the customer’s expectation a product will work as intended each and every time they use it. Performing this testing gives the manufacturers the confidence to stand behind their product and quantify its performance before being released. This is just a brief introduction to what we do and why we do it, but I hope it is interesting to you, looking past the confines of your particular niche.

Finding the Right Grip for Performing Tensile Tests on Braided RopeToday’s tale comes from the world of textile cords, notoriously difficult materials to test due to their high strength and often slippery surface. More specifically, we were tasked with testing braided rope used in maritime applications – tethering a boat to the dock. Being green to boating, I did a bit of prior research to better grasp how they are used in the real world and how much tension they could see in use. We first ran through our standard cord style grips, which use pneumatic pressure to clamp the material and an integrated capstan to wrap the cord around, distributing the clamping stresses. This configuration led to countless jaw breaks and premature failures. Clearly, we needed a custom solution for this problem, so we worked with our Engineered Solution Group. Inspiration was drawn from the docks, incorporating a cleat into the design, mimicking how a boat would be anchored.

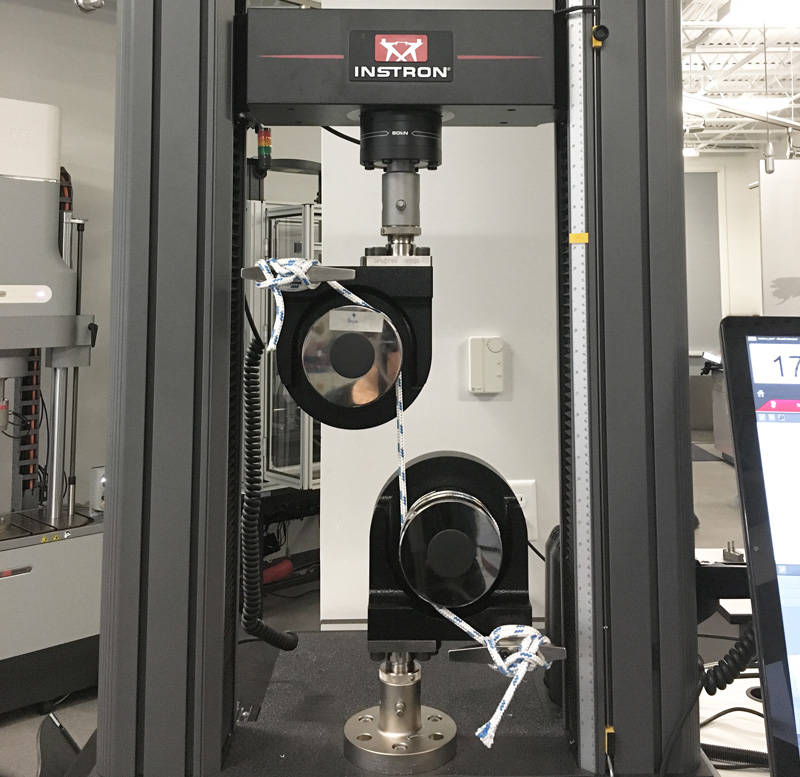

A couple weeks and some serious machining time later, we had a prototype to test the stubborn material. The capstan had machined grooves to further the stress and a cleat to tie the material off rather than a gripping mechanism. The next challenge was learning to tie a cleat knot through some very helpful online videos – a testament to the peculiarity of the job. After running trials with weaker material we had lying around, perfecting the technique, we were ready. We hit start, stepping back to maintain a safe distance since this stuff snapped at failure. The test was painstaking slow, but we had visual confirmation everything was working as intended. The knot on the cleat tightened until the rope was completely taught and then SNAP – the rope broke within the gauge length. The loads for the thickest rope topped out at nearly 7000 pounds or 31 kilonewtons. Documenting everything, we end all testing with a report outlining our solution and the results. Ultimately, we were able to create a new style of grip purpose-built for testing strong braided ropes and I was able to add another card to my bizarre rolodex of applications.